The skyrocketing costs of professional indemnity insurance (PII) and widespread exclusions from cover are causing significant pain across the industry. Responses to the AJ’s recent survey suggest the ongoing and worsening crisis even threatens to send practices under.

‘With the effect of Covid-19 on turnover, any further premium increases will make our business commercially unviable,’ one North West-based architect says.

These are fears shared by an alarming number of architects, according to the AJ’s study. As a partner in a London practice says: ‘PII is a time-bomb facing our profession – there will be many practices facing closure.’

Advertisement

The data backs this up. The survey of just under 200 businesses, carried out in December and January, showed practices are being quoted new premium prices that are, on average, three times higher than the cost of their previous policy renewal. And there is another worrying issue: only a small minority of practices have comprehensive insurance, with more than half (57 per cent) accepting exclusions relating to fire safety – limiting what they can work on and potentially leaving them on the hook for any historic claims.

‘This crisis poses significant risks to practices, clients and the public,’ says RIBA president Alan Jones. ‘We are seriously concerned about the rising costs of PII and growing prevalence of fire safety exclusions.’

So exactly how bad have things already got and what now for insurance costs and exclusions? What caused this crisis? And what, if anything, can be done to help?

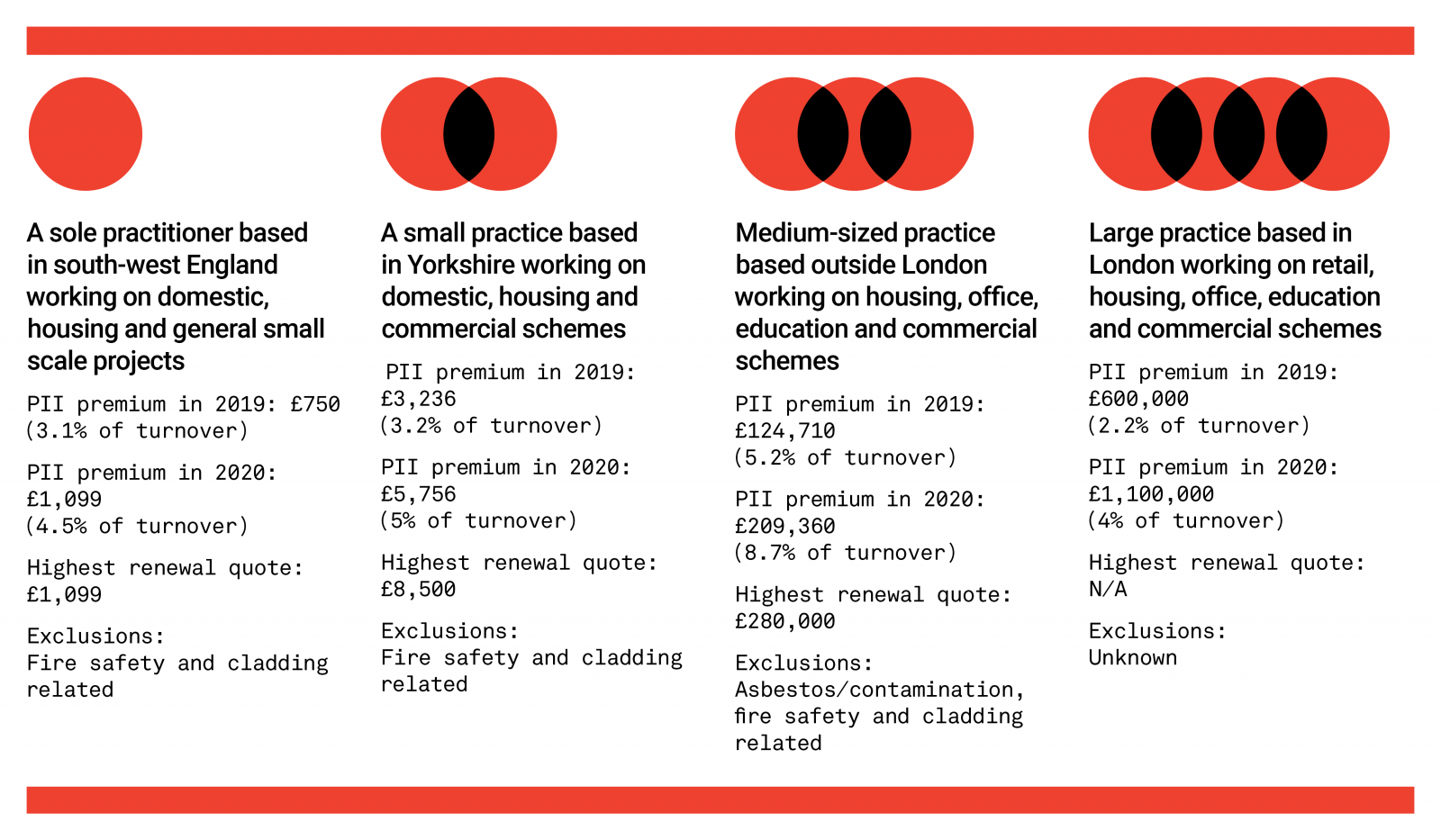

‘The cost of insurance is out of control’

According to the AJ’s survey, practices are on average reporting quotes 213 per cent higher than the amount they previously paid for PII. Analysis of the data reveals that architects spent an average of 2.3 per cent of their turnover on PII in 2019. Last year that had risen to 3.9 per cent. But the situation for many practices is already a lot worse, with some reporting eye-watering 1,000 per cent increases in insurance cost, with PII policies equating to 10 per cent of revenue.

No less than 90 per cent of those polled said they were concerned about the cost of PII, with more than half of architects (52 per cent) admitting they were ‘very worried’.

Advertisement

‘It feels like the cost of insurance is out of control and can be increased irrespective of the economics [of practices],’ said one respondent to the anonymous questionnaire. Another said PII costs approaching 5 per cent of turnover were ‘simply not sustainable’ while profit margins remained in the ‘low single digits’.

An architect based in the east of England told the AJ he thought PII costs were going to prevent expansion of his practice. ‘We are looking to move into larger work and have been asked by a number of potential clients to increase our level of cover from £1 million to £5 million,’ he said.

‘I am concerned that, given that our current cost has doubled, increasing cover to £5 million will represent a substantial cost increase that will be difficult to manage. The potential result is that we need to decline work of a larger nature and fee, limiting our ability to grow as a practice.’

Many respondents acknowledged that, while the increased cost should be passed on to clients, in a competitive marketplace the burden was often falling on their own profit margins instead. The rise also comes at a turbulent time, with many practices feeling the pressures on revenue and margins caused by Covid-19 disruptions.

‘I am worried that a new benchmark has been set and there is not sufficient external review of the sector to ensure that there is a competitive market to keep costs to an acceptable level,’ one survey respondent said.

As well as being hit by higher costs, practices are also being hit by an increasing number of exclusions to their PII coverage – with 65 per cent telling the AJ they had new or expanded exclusions last time they renewed.

This figure is a troubling 11 percentage points higher than that recorded in a poll carried out by the ARB and Savanta ComRes in April 2020 (where 54 per cent of practices said they had seen fresh restrictions to their coverage).

And it is a problem that potentially has more profound implications for architects than the rising cost.

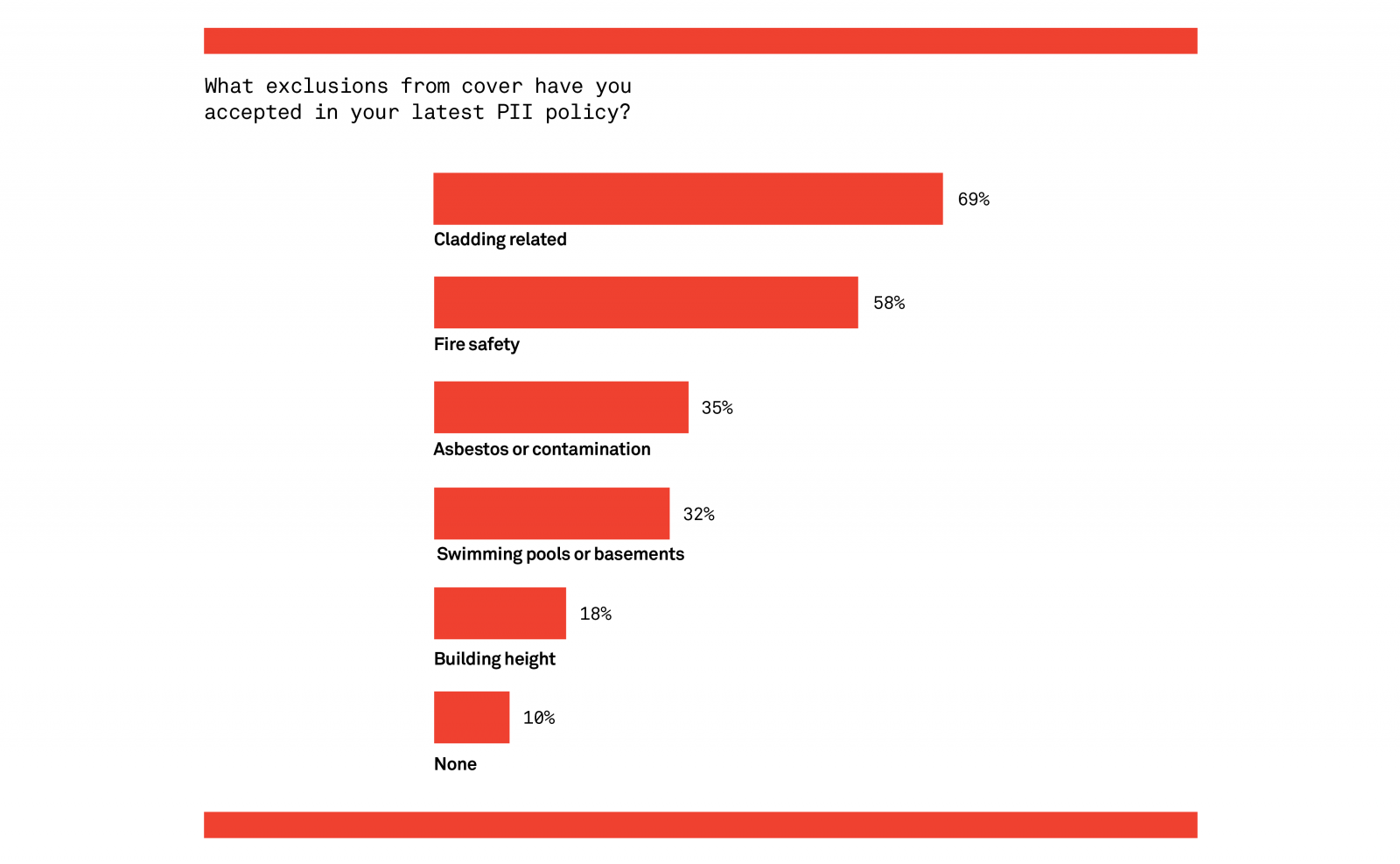

The most common exclusion clauses relate to cladding (69 per cent) and fire (58 per cent). However, the AJ survey also revealed widespread exclusions relating to asbestos or contamination (34 per cent) and work on basements (32 per cent).

Fire exclusions are a particular worry. ‘At present we cannot design or specify anything related to fire, including everything from strategy to fire-rated wall build ups and fire doors,’ said one survey respondent. Another said they couldn’t ‘offer the most basic design service if fire safety is excluded’.

A director of a North West-based company said their exclusion was ‘very vague’ and that their insurers couldn’t ‘tell us what this may or may not cover’.

‘In the last three years

our PII premium has risen from

£1,500 to £4,860’

Director of North West-based practice

With few standard clauses for excluding liabilities relating to fire, or indeed anything else, practices are all insured to a different extent. There is a dangerous likelihood some firms do not have the minimum level of PII demanded of practices and practitioners by the Architects Code, which expects an ‘appropriate level of PII’ that ‘remains adequate to meet a claim’.

ARB director of regulation Simon Howard is concerned. ‘Architects have reported the inconsistent terminology used in exclusion clauses, which causes them difficulties in understanding what liabilities they are covered for, and in comparing competing products in the market,’ he says.

‘Insurance remains absolutely vital to protect architects, and the people who will use the buildings they design. We are encouraging architects to seek expert advice, for example from their brokers, as to whether the policy will provide adequate cover for their needs.’

Even large practices are finding this a problem. Stride Treglown managing director Darren Wilkins says his practice had no offers for an ‘unfettered’ PII policy last time it renewed but was lucky to have some aspect of fire design insurance.

Meanwhile PRP, which includes cladding and tower blocks among its specialisms, spent three months working on a suite of documents demonstrating its risk management processes with its broker before being able to get PII covering fire safety.

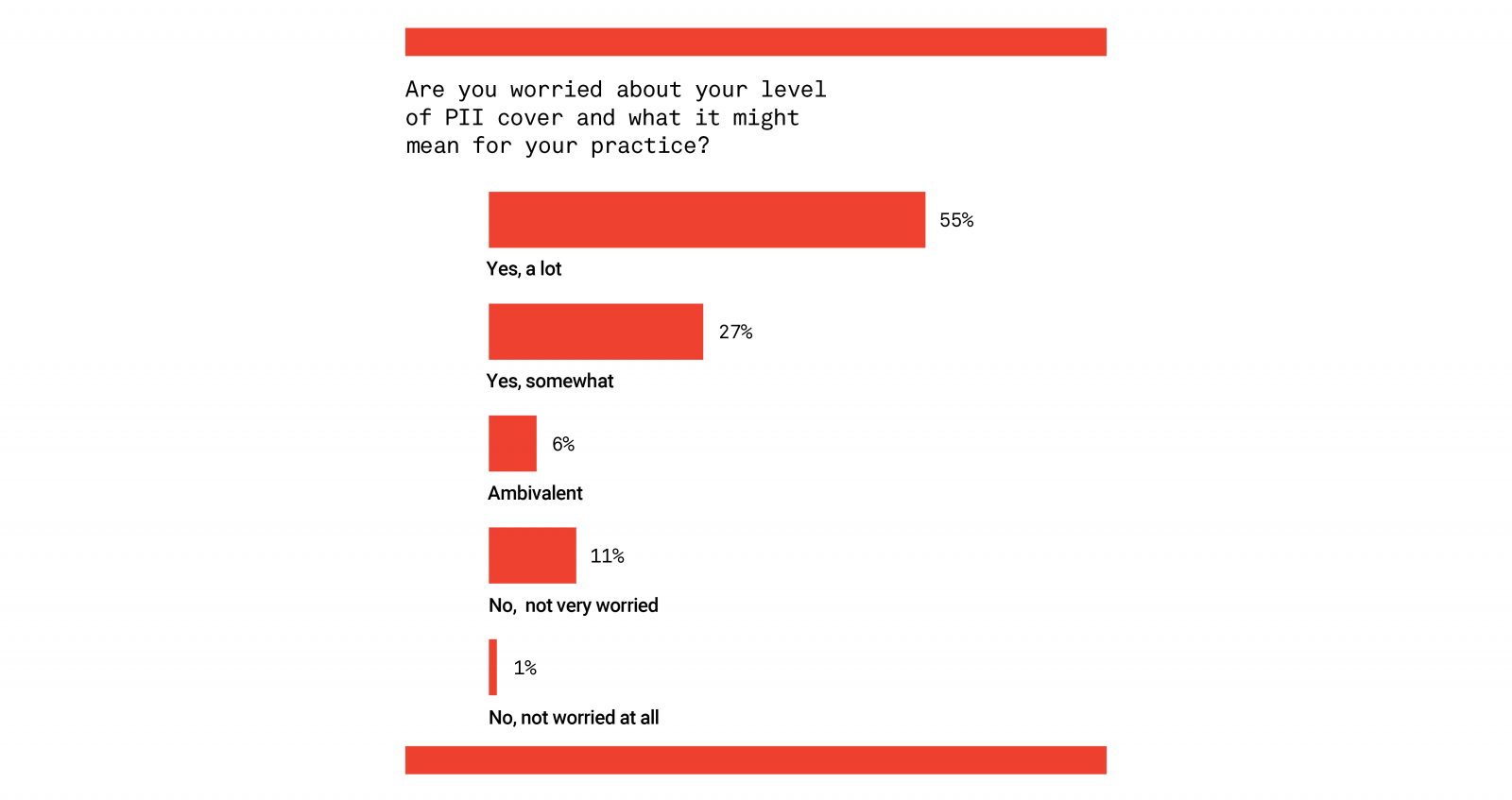

A total of 55 per cent of practices polled by the AJ said they were very worried about what their level of PII cover means for their business, while a further 27 per cent said they were ‘somewhat worried’.

Widespread problems with architects’ non-insurance threaten building owners and tenants who are exposed to uninsurable risk, while practices are put at increased risk of direct litigation costs which they are unlikely to have sufficient assets to meet. Furthermore, architects are put at an increased risk of being pursued directly where all other avenues to recover costs fail.

With insurance often not covering problems relating to fire, and in particular to cladding, architects risk being accused of liability for a building they have worked on in the past, and having to cough up on legal fees just to prove they are not responsible.

What caused the crisis? Is Grenfell the only reason?

The sector is not alone in feeling an insurance cover crunch. ‘The whole PII market has hardened,’ says Laura Hughes, policy manager for general insurance at the Association for British Insurers (ABI). ‘This covers construction, but also other sectors where professionals are required to purchase it, such as brokers, solicitors and financial advisers.’

She adds: ‘What we have seen is a reduction in the number of insurers offering to underwrite risks, creating less competition and more concern from those left in the market, which often results in increases in cost of premium as well as excesses and limitations.’

One of the key reasons behind this is the ‘Decile 10’ review launched by Lloyd’s of London in October 2018. Lloyd’s outlined plans to clamp down on loss-making or low-margin syndicates, prompting several syndicates to withdraw from PII lines of business.

Coronavirus has further hampered any appetite for risk in the insurance market, with insurers and underwriters forced to pay out for cancellation of flights and events, as well as on interruption to businesses and trade credit.

But, despite a general hardening of the professional indemnity market, construction has had a particularly torrid time. Over the past decade, construction has yielded poor margins for insurers, says the ABI’s Hughes, as reserves are swallowed up by infrequent but extremely expensive problems with projects.

Then in 2017, the fire at Grenfell Tower in west London claimed the lives of 72 people.

After the tragedy, the government identified 460 high-rise towers with combustible ACM cladding similar to that used on Grenfell Tower. More could yet be discovered.

What did average insurance

payments in 2019 equate to

in terms of percentage of

that year’s turnover?

2.3%

This figure does not include buildings with other unsafe cladding systems, nor any buildings with ACM cladding under 18m in height. The discovery of scores of dangerous buildings creates a bundle of possible new liability, or risk, to architects, which insurers are inevitably keen to avoid.

‘The potential claims scenarios are so significantly high that the level of premium an insurer would need to charge has become unaffordable for those in the industry,’ adds Hughes. ‘In many circumstances the potential claims scenarios are a little bit unknown, but they have the potential to be really, really significant.’

Even where claims do not come to fruition, this risk has reduced capacity in the PII market as insurance companies have received an avalanche of notifications of potential claims relating to cladding, all of which must have money set aside to cover potential losses – thus removing liquidity which could be used for other insurance.

The Grenfell Tower tragedy has exposed more than just dangerous buildings; it has revealed systemic failure – and ongoing risk – in the way buildings are designed and constructed in the UK.

‘At heart, the core problem [around PII] is government’s failure to maintain an effective regulatory system,’ argues Jack Pringle, chair of the RIBA and former regional director for Europe and the Middle East at Perkins&Will. ‘The Grenfell Tower Inquiry has revealed that the [regulatory system] they allowed was complex, ambiguous, easily cheated by the unscrupulous and inadequately enforced.’

Mark Brundell, head of professional indemnity at insurer Zurich, agrees that ‘there are understandable concerns about past, present and future contracts’ as ‘the construction sector is having to deal with some very ambiguous regulations’.

He says: ‘The government’s retrospective interpretation of Approved Document B, coupled with the absence of a clear set of regulations, means that there is some confusion surrounding what is allowed and what is not allowed.’

But he also argues that the market for architects’ PII was ripe for contraction anyway, given that practices had experienced premium rate reductions every year (except 2008/9) for more than a decade since 2005.

‘Rates have been at what some would consider unsustainable levels for many years,’ he says. ‘Other professions pay substantially more per pound of exposure than architects. In this sense there is no market failure.’

What can be done about the PII crisis?

Architects have suffered from higher costs and lower competition for their PII cover before: in the 1980s and, to a lesser extent, after the turn of the millennium. Professional indemnity markets are cyclical.

But that does not necessarily mean the current problem is about to get better; the level of risk architects are exposed to – and the corresponding reticence of insurers to take it on – seems likely to stick around.

‘It does seem that there is little immediate prospect of improvement,’ says Pringle. ‘PII premiums are likely to increase as a proportion of turnover [but] it is hoped that the breadth of limitations and exclusions can be reduced so that they at least better reflect the real areas of risk in relation to external walling systems, rather than blanket fire safety provisions.’

Judith Hackitt, author of the government’s review into the Building Regulations and chair of the yet-to-be-established Building Safety Regulator, has suggested the new regulatory system will help ease the crisis – a view widely held by trade bodies and insurers.

She told the AJ in October: ‘With professional indemnity cover, part of the current problem lies in lack of clarity about who is responsible for what ... the new regulatory regime will provide greater confidence in better quality and safer buildings, which should ease the situation.’

But the Building Safety Bill has not yet been presented to Parliament. The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) is currently considering a report by its select committee counterpart, following the committee’s scrutiny of the draft bill.

The bill is therefore unlikely to receive Royal Assent until at least the second half of 2021, with new regulations coming in some time after that. The delay is part of the reason architects have called for the government to intervene in the PII crisis now.

A government source told the AJ that the MHCLG was investigating ‘commercial and government’ solutions to make PII more available to a range of construction professions, in dialogue with insurers and trade bodies.

An intervention is something that has been called for by both built environment and insurance trade bodies. The RIBA has said the government should broker a short-term solution to the PII crisis, calling for a re-insurance scheme for existing high-rise residential buildings.

The ABI has also told the government there is a ‘very hard market’ across construction PII, and that a government insurance scheme would help with issues such as remediation.

But it is understood that the government’s initial priority is to ensure fire engineers and consultants can get PII, as this is key to the speedy remediation of buildings with combustible external walls.

What does the average 2020 premium

equate to in terms of percentage

of this year’s projected turnover?

3.9%

Pragmatists warn that it is fanciful to expect the government to quickly step in and underwrite the entire construction industry at a time when it has so many competing financial and logistical pressures.

However, that does not mean there is nothing it can do. PII policies currently contain dozens of slightly different exclusion clauses which offer architects differing amounts of protection, even when they are aiming to do a similar thing – for instance protecting an insurer for liability relating to combustible cladding.

The government could get major insurers around a table and encourage them to agree on terms and definitions for exclusion clauses. This would make the market more transparent and competitive, helping architects understand whether a given policy offers effective protection, or whether another would offer better value.

Another potential solution is individual project insurance, where developments rather than the delivery team members are insured against any problems.

It’s a model of insurance and procurement that its supporters claim ends buck-passing and encourages collaboration between a project team. But it is currently only seen as effective for larger projects that carry a lot of risk. Insurers are generally uninterested in pricing up lots of medium-sized jobs and are put off by project insurance typically lasting 20 years – during which time building regulations and requirements could get tougher, prompting pay-outs.

To some extent, architects can also take matters into their own hands to address their PII burden – by demonstrating to insurers and brokers that they are a good risk.

Former RIBA president Jane Duncan notes: ‘It’s certainly been rare for architects to keep on top of quality procedures and fire safety design processes in order to demonstrate to insurers sufficient in-house skills and knowledge to assuage doubts and reduce risk.’

Scott Sanderson, a partner at PRP, says his practice agreed a ‘series of presentations in document form’ with brokers and insurers.

He explains: ‘It included anything related to fire, our leadership team and an outline of their responsibilities, the work we are doing to manage fire safety design, our risk management and what extra steps we are taking to manage oversight risk, plus a standalone fire safety audit.’

Mandatory competence tests for all architects, which are set to be introduced by the ARB, should also help reassure insurers that architects are capable of properly managing risk going forward.

Tests are also being brought in by 2023 for RIBA chartered members, with a Fire Safety Design Risk Management Guide and pilot Health and Life Safety test set to be published soon.

Time is ultimately a large part of what will restore capacity in the insurance market, and bring back reasonably priced, comprehensive PII to architects.

New building safety regulations, competence tests and, post-pandemic, a more certain economy are all likely to help ease the current situation.

But for some practices struggling to make ends meet – or which are hit with historic cladding claims – time may not be on their side.

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

Leave a comment

or a new account to join the discussion.